|

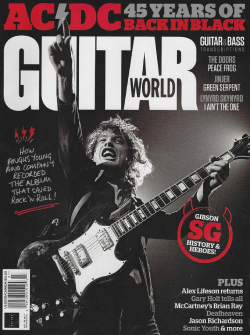

Guitar World Magazine - July 2025 by Andrew Daly |

Envy of None guitarist Alex Lifeson brings his chops back to the forefront on Envy of None’s sophomore release, Stygian Wavz.

Plus a new Rush box set, hangin' with Geddy Lee, Lerxst gear, and more.

WHEN RUSH CAME off the road in 2015, Alex Lifeson’s interest in guitar waned. And when Rush drummer Neil Peart died of cancer nearly five years later, Lifeson entered a period of mourning, meaning guitar completely took a backseat. But things began to change when fellow Canadian (and Coney Hatch bassist) Andy Curran reached out to Lifeson, asking him to provide scratch guitar tracks to help bring a few of his skeletal compositions to life. At first, Lifeson thought nothing of it; soon, however, a new band — Envy of None — was born.

Lifeson says he was reticent during the recording of the band’s self-titled first album back in 2022, which led him to take something of a six-string backseat and focus on creating sounds that “didn’t sound like a guitar.” Call it a case of easing into things after spending most of his adult life beside Rush’s Peart and Geddy Lee, who he considers his brothers. But nothing could change the fact that Rush was over.

“You can’t change the past,” Lifeson says. This meant that if Envy of None were to make a second album, he’d have to dive in, take the training wheels off and let it rip.

Lifeson did just that, as heard on 2025’s Stygian Wavz, an album that, for a time, didn’t even appear to be in the cards. “I didn’t expect, really, to make a second record after the first one, which was just an exercise more than anything,” Lifeson says. “But this album has got our soul in it. We’re not just a group of musicians in some sort of co-op unit. We’re functioning like a band, we sound like a band, and that was the result of being freer and more open, which you can do on a sophomore record.”

As a lifelong gearhead with a new sense of interest in the process of creation, Lifeson turned to his stable of toys to bring his guitar playing to the forefront. “It’s just so much fun to create moods, colors and textures,” he says. “I have loads of crazy gear and old pedals. There are just so many things now that you can use to manipulate sounds. It’s really a treat for me to work that way.”

Listening to Stygian Wavz, one gets the sense that Lifeson, a guitarist whose playing has always served the song, has regained his footing as a titan of rock guitar. That’s not to say he’s overplaying; he’s merely expressing himself in ways his fans are used to.

Listening to Stygian Wavz, one gets the sense that Lifeson, a guitarist whose playing has always served the song, has regained his footing as a titan of rock guitar. That’s not to say he’s overplaying; he’s merely expressing himself in ways his fans are used to.

Regardless of what Envy of None does (or doesn’t do), Rush will always loom large in Lifeson’s mind. But even though he’s proud of his past, he says he’s focused on his new band, meaning we’ll just have to keep on waiting for one of those rumored Rush reunions. Still, Lifeson doesn’t entirely punt on the idea. “We [Lifeson and Lee] get together — we do stuff together. Sometimes I go over there, and we’re going to jam or something, and we end up just drinking coffee and laughing, you know? That’s a beautiful part of our relationship. Will something come of it? I don’t know. Who knows? But I know I’m really happy doing [Envy of None].”

Stygian Wavz definitely has a different flavor from the band’s 2022 debut.

Yes, it does. The first one, I think, I don’t know… it was a new thing for us. We’d never worked together, and songs developed the way they did. It had that cinematic, atmospheric thing, and I loved it. But this one sounds more like we’re a unified unit — more like a band.

There’s definitely cohesiveness, and it sounds like you’re stretching out as a player, with some signature touches and ethereal sounds. What’s the secret sauce?

Well, I start off with a little bit of cannabis. [Laughs] Then, I just go, you know? I’ve always loved that, even in Rush; whenever I had the chance, I tried to do little atmospheric intervals wherever I could. And with the first Envy of None record, I had a free license. Probably 70 percent of the guitar stuff on that record doesn’t sound like a guitar. I made an effort to do that because I wanted to do that — I wanted it to not sound like a guitar.

You’ve found a balance between that and letting loose on this record.

With this record, I take those moments and try to incorporate them in more of a rock sense. Then, working with [vocalist] Maiah [Wynne], we work very closely together. She’s a real inspiration for me and naturally drives me along that path.

A song like “Not Dead Yet” has got that ethereal thing, but there’s also some twang. How did you approach that?

When I first got the original idea, Andy and [guitarist/keyboardist] Alf [Alfino Annibalini] had written a very simple sketch of what they were after. I loved it right from the get-go. Part of my history dates back to the Toronto scene in the Sixties between the hippies and the R&B guys. There was a real movement for Toronto funk, and that’s what I heard in the first few bars of that song. I wanted to create something along those lines.

What gear did you break out to do that?

I used a Tele for the main track; I have all my analog gear here in the studio — my compressors, preamps and three or four amps. And I have an enclosure with a single Celestion 12. This is all in my apartment. I’ve got lots of tools here to work on anything and develop anything. With that song, I wanted to keep that funky groove; then, once it went off into the chorus, the heavy guitars came in, and we followed up with the cleaner, James Bond-ish thematic outro.

Speaking of heavy guitars, “Under the Stars” has a lot of that — but it’s also got a very quintessential “less is more” solo, which is something you’ve always done very well.

That’s been number one with me for my whole life. It’s all in service of the song.

When I’m constructing solos, I’m thinking about the song, like, “How does it fit into the song? How does it reflect what the emotional character of the song is?” That’s really important to me. I don’t set out to go, “I’m gonna play the fastest I can possibly play.” Maybe in the early days I was sort of like that, but it’s not about flashiness and trying to out-flash some other guitar player. It’s all about the song.

What did you hear in “Under the Stars” that led to your approach?

When I first heard that section, we discussed it, and everybody said, “It’d be great to have a guitar solo.” I’ve been sort of reluctant to play solos because of that whole attitude, but on this record, I thought, “You know what? I’m going to go back to playing solos and constructing them because it’s going to help the song.” So that one was kind of different for me. The volume and tone pots were turned down, and I played with my fingers instead of a pick. Then I stole a little David Gilmour lick there; it’s very emotional and very powerful.

You mentioned being reticent in terms of playing solos. I assume that on the first record, there was a concern that your lengthy track record with Rush could weigh down the project. Have you moved past having to bear the weight and legacy of Rush and be more free as a guitarist?

That’s a great question and observation. With the first record, I was very reticent about being too flashy or too much of a guitarist, you know? I made an effort to create sounds that we un-guitar, which was a great challenge, fun and suited the record. But with this record I felt more confident I could play a more traditional role. My response was to start including more solos and being more open about the guitar parts that I was writing.

Is that a lot different from your role within Rush since you’re not the sole guitarist in Envy of None?

In Rush, I was the only guitar player. In this band, Alf plays a lot of guitars, and Andy throws down a guitar every once in a while. I’m a little more free because I’ve a commitment to this unit as a band. When I got the mixes back, I thought, ‘Oh, my God, we’ve become a band.”

After spending all those years in Rush and having it end the way it did, there must have been a level of trepidation to where trying something new felt insurmountable or that it might impact the way you’re viewed.

You know, to my core, I’m just a musician. I’m just a guitar player. I love playing guitar. I play guitar — I don’t know — three or four hours a day, and I always include an hour before I go to bed. It’s just a discipline I’ve adapted, which I’m very happy about because I’m not a very disciplined person. [Laughs] I’ve really come to love playing guitar more than ever. Then, working on this project to where I’m feeling a little more comfortable, I’m not in the shadow so much of Rush. I mean… I’m so proud of what I did in Rush and all that we did, but at the end of it, I’m still that guy who likes to play in a band. It doesn’t matter what form, just as long as I love it and I respond to the ideas — and there are great ideas among the four of us.

As someone who isn’t so disciplined, and after being a working musician for more than 50 years, it’s incredible to hear that you’re still playing for hours a day. What keeps you inspired?

After Rush finished in 2015, I really didn’t play much. I did a little bit afterward, but honestly, I really didn’t play for months. It wasn’t until Andy reached out to be in 2016, saying, “I’m working on some music. Would you mind putting some guitars down?” that I started to play more. I did that for him, and it wasn’t particularly tight, but it gave him an idea, a sketch, of what a guitar sounded like with the songs he was writing. That was that. But he came back later and said, “I’ve got a couple of other songs. Would you mind doing the same thing?” Then, Envy of None started to happen. And Neil [Peart] was sick; I wasn’t inspired to play very much when Neil was sick. I noodled a bit because I didn’t want my fingers to go completely rubbery, but my heart wasn’t in it with my brother being ill in that way.

Did Neil’s passing and, of course, mourning him help you move forward?

When he passed, it was like, “I gotta move forward.” That was part of the whole grief process for me. Usually, grief lasts for a solid year, and then, I say to myself, “Okay, you’ve got to move forward. You can’t change the past.” It was around that time that I really dove back into playing much more regularly. In the last year, I’ve adapted this more manic playing, where I’m playing for hours every day — and I love it.

Was it a challenge to get back into proper playing shape?

Well, my fingers feel better! I’m 71; I’m not going to play like I did when I was 21 — or 51, for that matter. [Laughs] But I’ve found that my fingers are coming back; they’re grateful to me for doing this and getting them back into shape. It’s a long road when you’re at this age and battling the things that come with advanced years, but my fingers feel so much better than they did six months ago. I feel so much more confident in my playing. I feel confident. I feel happy. I feel reborn in terms of playing. It’s a good place for me right now.

Can you describe the player you are today? We know what you’re capable of and what you’ve done, and with that, listeners have an expectation and perception of you. Who is Alex Lifeson the guitarist in 2025?

I know where I came from, and I know what I was like as a player for the bulk of my main career. Now, I’m more of a sensitive player. I don’t have the same kind of expectations. I’ve never been very confident, to be honest with you, as a player. I’ve always felt like I had to work hard, and maybe I didn’t appreciate that I have a natural talent for playing guitar.

Given the breadth of your catalog, it’s hard to believe you lacked confidence.

I always felt like I had to work really hard if I wanted to be good at it. I kind of discounted my natural ability, and I’m more aware of that now. I find that when I’m doing takes, I’ve always been an early-take guy. My best work is in the first five or six takes, particularly the solos. But I’m finding now that the first couple of takes are really satisfying.

Having more confidence has to help with the age-related roadblocks you mentioned.

My playing has changed quite a bit. I don’t think I’m as dexterous; I don’t think I have the precision and speed I had, but that’s coming. The more I play, the more creative I feel in how I envision the part I’m trying to do and with the part I’m writing. That’s why I’m getting results quicker these days.

Are there any updates to your stable of signature gear?

Yeah — we had the [Lerxst] Limelight come out, the Grace, and now we have the Freewill, which is the original modified Strat I had in 1979. So, that’s the black version of all these three guitars. That’s coming out next. And Epiphone has a few things they want to release; they’d like to do a reissue of the ES-335, and Gibson wants to do an acoustic and some other things. On the pedal front, we have the [Lerxst] By-Tor and the Snowdog. We’re working on a chorus and probably a delay. I have some ideas about an amp pedal, you know, incorporating what we do with the Lerxst amps but in a smaller enclosure. So yeah… there’s always something in the world of gear. I’ve always been a gearhead!

Do you mostly lean on your new gear when recording, or do you use a lot of your tried-and-true gear from your Rush days?

There are definitely go-to’s that I prioritize, but I also just like grabbing something that I don’t think is the “right” thing and seeing how that works. Like, I have the first guitar I ever owned, which my parents bought for me in 1967 for $57. It’s just a cheap Japanese guitar that I had refinished. I pull it up for some things; it’s kind of like a Jack White sensibility, like, “I’ll take this crappy guitar and see what happens.” So far, I haven’t had much success, to be honest. [Laughs] But you get what I’m saying. Sometimes, I’ll go for a P90; I’m not normally inclined in that way with guitars, but now I realize that tonality is what it’s all about. I create different tones.

Is there one guitar or amp you favor?

I’d probably say my ES-335, the Lerxst guitars and a couple of my Teles. And then, on the amp front, I’ve got a bunch of them. I’ve got a Marshall, my Lerxst amps, Bogner, a Mesa Boogie Mark V and — like I said — I have an enclosure built with a single Celestion 12. Then I’ve got my Universal Audio compressors and about a dozen good acoustics. I’ve been collecting gear for 50 years, so I’ve got a good arsenal of gear here in my apartment. I’m covered.

On the Rush side of things, there’s a new box set, Rush 50. What’s the story there?

On the Rush side of things, there’s a new box set, Rush 50. What’s the story there?

We [Alex and Geddy] don’t get involved too much in how that’s all put together. Everybody knows what we want to do, and we have good people who know what we want to create. And the record company, Anthem, has been amazing. They don’t have to get our approval; they can just go ahead and do all this stuff. But they always ask us. They want to make sure we’re happy and satisfied with everything. So we do engage, and we do change things up, and we do get clarification on stuff and all of that. But this particular package is pretty remarkable. It’s a beautiful package with great, great stuff in it. I’m really looking forward to its release.

Has your newfound comfortability and growing confidence in Envy of None as a functioning band given you the license to put to bed the hope that you and Geddy will work together again? Is that officially in your rear view mirror?

Well, you know, “in the rear view mirror” is maybe a little harder than… I would say I’m so proud of my past and all of that. But I like playing. I like writing. I like working with people. Geddy is my best friend. I talk to him every day, you know?

Does that mean Envy of None has a long-term future?

We’re likely going to start the third record the day after this one releases. So I’m in a good space. I’m working on another project for a documentary on the Great Lakes with some brilliant musicians. That’s really a lot of fun, but there’s no hard deadline, so we’re moving slowly but in a really good direction. And I’m working with another female artist; I always pick up little gigs here and guest on other people’s albums. I’m a working musician.

-| Click HERE for more Rush Biographies and Articles |-